Sturm–Liouville theory

In mathematics and its applications, a classical Sturm–Liouville equation, named after Jacques Charles François Sturm (1803–1855) and Joseph Liouville (1809–1882), is a real second-order linear differential equation of the form

-

![-\frac{d}{dx}\left[p(x)\frac{dy}{ dx}\right]%2Bq(x)y=\lambda w(x)y,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/8e023ab76ae6eb1f5d6986c2e78f5b1c.png)

(

where y is a function of the free variable x. Here the functions p(x) > 0, q(x), and w(x) > 0 are specified at the outset. In the simplest of cases all coefficients are continuous on the finite closed interval [a,b], and p has continuous derivative. In this simplest of all cases, this function "y" is called a solution if it is continuously differentiable on (a,b) and satisfies the equation (1) at every point in (a,b). In addition, the unknown function y is typically required to satisfy some boundary conditions at a and b. The function w(x), which is sometimes called r(x), is called the "weight" or "density" function.

The value of λ is not specified in the equation; finding the values of λ for which there exists a non-trivial solution of (1) satisfying the boundary conditions is part of the problem called the Sturm–Liouville (S-L) problem.

Such values of λ when they exist are called the eigenvalues of the boundary value problem defined by (1) and the prescribed set of boundary conditions. The corresponding solutions (for such a λ) are the eigenfunctions of this problem. Under normal assumptions on the coefficient functions p(x), q(x), and w(x) above, they induce a Hermitian differential operator in some function space defined by boundary conditions. The resulting theory of the existence and asymptotic behavior of the eigenvalues, the corresponding qualitative theory of the eigenfunctions and their completeness in a suitable function space became known as Sturm–Liouville theory. This theory is important in applied mathematics, where S–L problems occur very commonly, particularly when dealing with linear partial differential equations that are separable.

Contents |

Sturm–Liouville theory

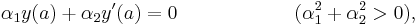

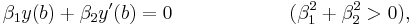

Under the assumptions that the S–L problem is regular, that is, p(x), w(x) > 0, and p(x), p'(x), q(x), and w(x) are continuous functions over the finite interval [a, b], with separated boundary conditions of the form

-

(

-

(

the main tenet of Sturm–Liouville theory states that:

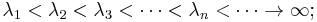

- The eigenvalues λ1, λ2, λ3, ... of the regular Sturm–Liouville problem (1)-(2)-(3) are real and can be ordered such that

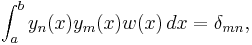

- Corresponding to each eigenvalue λn is a unique (up to a normalization constant) eigenfunction yn(x) which has exactly n − 1 zeros in (a, b). The eigenfunction yn(x) is called the n-th fundamental solution satisfying the regular Sturm–Liouville problem (1)-(2)-(3).

- The normalized eigenfunctions form an orthonormal basis

- in the Hilbert space L2([a, b],w(x) dx). Here δmn is a Kronecker delta.

Note that, unless p(x) is continuously differentiable and q(x), w(x) are continuous, the equation has to be understood in a weak sense.

Sturm–Liouville form

The differential equation (1) is said to be in Sturm–Liouville form or self-adjoint form. All second-order linear ordinary differential equations can be recast in the form on the left-hand side of (1) by multiplying both sides of the equation by an appropriate integrating factor (although the same is not true of second-order partial differential equations, or if y is a vector.)

Examples

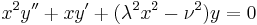

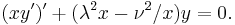

The Bessel equation:

can be written in Sturm–Liouville form as

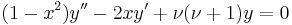

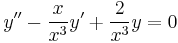

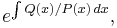

The Legendre equation,

can easily be put into Sturm–Liouville form, since D(1 − x2) = −2x, so, the Legendre equation is equivalent to

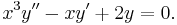

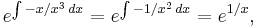

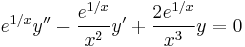

Less simple is such a differential equation as

Divide throughout by x3:

Multiplying throughout by an integrating factor of

gives

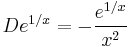

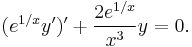

which can be easily put into Sturm–Liouville form since

so the differential equation is equivalent to

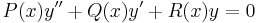

In general, given a differential equation

dividing by P(x), multiplying through by the integrating factor

and then collecting gives the Sturm–Liouville form.

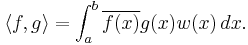

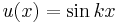

Sturm–Liouville equations as self-adjoint differential operators

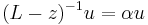

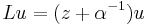

The map

can be viewed as a linear operator mapping a function u to another function Lu. We may study this linear operator in the context of functional analysis. In fact, equation (1) can be written as

This is precisely the eigenvalue problem; that is, we are trying to find the eigenvalues λ1, λ2, λ3, ... and the corresponding eigenvectors u1, u2, u3, ... of the L operator. The proper setting for this problem is the Hilbert space L2([a, b],w(x) dx) with scalar product

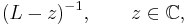

In this space L is defined on sufficiently smooth functions which satisfy the above boundary conditions. Moreover, L gives rise to a self-adjoint operator. This can be seen formally by using integration by parts twice, where the boundary terms vanish by virtue of the boundary conditions. It then follows that the eigenvalues of a Sturm–Liouville operator are real and that eigenfunctions of L corresponding to different eigenvalues are orthogonal. However, this operator is unbounded and hence existence of an orthonormal basis of eigenfunctions is not evident. To overcome this problem one looks at the resolvent

where z is chosen to be some real number which is not an eigenvalue. Then, computing the resolvent amounts to solving the inhomogeneous equation, which can be done using the variation of parameters formula. This shows that the resolvent is an integral operator with a continuous symmetric kernel (the Green's function of the problem). As a consequence of the Arzelà–Ascoli theorem this integral operator is compact and existence of a sequence of eigenvalues αn which converge to 0 and eigenfunctions which form an orthonormal basis follows from the spectral theorem for compact operators. Finally, note that  is equivalent to

is equivalent to  .

.

If the interval is unbounded, or if the coefficients have singularities at the boundary points, one calls L singular. In this case the spectrum does no longer consist of eigenvalues alone and can contain a continuous component. There is still an associated eigenfunction expansion (similar to Fourier series versus Fourier transform). This is important in quantum mechanics, since the one-dimensional time-independent Schrödinger equation is a special case of a S–L equation.

Example

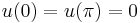

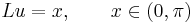

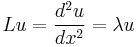

We wish to find a function u(x) which solves the following Sturm–Liouville problem:

-

(

where the unknowns are λ and u(x). As above, we must add boundary conditions, we take for example

Observe that if k is any integer, then the function

is a solution with eigenvalue λ = −k2. We know that the solutions of a S–L problem form an orthogonal basis, and we know from Fourier series that this set of sinusoidal functions is an orthogonal basis. Since orthogonal bases are always maximal (by definition) we conclude that the S–L problem in this case has no other eigenvectors.

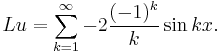

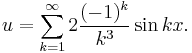

Given the preceding, let us now solve the inhomogeneous problem

with the same boundary conditions. In this case, we must write f(x) = x in a Fourier series. The reader may check, either by integrating ∫exp(ikx)x dx or by consulting a table of Fourier transforms, that we thus obtain

This particular Fourier series is troublesome because of its poor convergence properties. It is not clear a priori whether the series converges pointwise. Because of Fourier analysis, since the Fourier coefficients are "square-summable", the Fourier series converges in L2 which is all we need for this particular theory to function. We mention for the interested reader that in this case we may rely on a result which says that Fourier's series converges at every point of differentiability, and at jump points (the function x, considered as a periodic function, has a jump at π) converges to the average of the left and right limits (see convergence of Fourier series).

Therefore, by using formula (4), we obtain that the solution is

In this case, we could have found the answer using antidifferentiation. This technique yields u = (x3 − π2x)/6, whose Fourier series agrees with the solution we found. The antidifferentiation technique is no longer useful in most cases when the differential equation is in many variables.

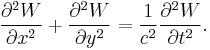

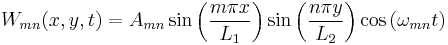

Application to normal modes

Certain partial differential equations can be solved with the help of S-L theory. Suppose we are interested in the modes of vibration of a thin membrane, held in a rectangular frame, 0≤x≤L1, 0≤y≤L2. The equation of motion for the vertical membrane's displacement, W(x, y, t) is given by the wave equation:

The method of separation of variables suggests looking first for solutions of the simple form W = X(x) × Y(y) × T(t). For such a function W the partial differential equation becomes X"/X + Y"/Y = (1/c2)T"/T. Since the three terms of this equation are functions of x,y,t separately, they must be constants. For example, the first term gives X"= X for a constant

X for a constant  . The boundary conditions ("held in a rectangular frame") are W=0 when x=0, L1 or y = 0, L2 and define the simplest possible S-L eigenvalue problems as in the example, yielding the "normal mode solutions" for W with harmonic time dependence,

. The boundary conditions ("held in a rectangular frame") are W=0 when x=0, L1 or y = 0, L2 and define the simplest possible S-L eigenvalue problems as in the example, yielding the "normal mode solutions" for W with harmonic time dependence,

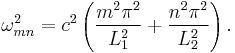

where m and n are non-zero integers, Amn are arbitrary constants, and

The functions Wmn form a basis for the Hilbert Space of (generalized) solutions of the wave equation; that is, an arbitrary solution W can be decomposed into a sum of these modes, which vibrate at their individual frequencies  . This representation may require a convergent infinite sum.

. This representation may require a convergent infinite sum.

Representation of Solutions and Numerical Calculation

The Sturm-Liouville differential equation (1) with boundary conditions may be solved in practice by a variety of numerical methods. In difficult cases, one may need to carry out the intermediate calculations to several hundred decimal places of accuracy in order to obtain the eigenvalues correctly to a few decimal places.

1. Shooting methods.[1][2] These methods proceed by guessing a value of λ, solving an initial value problem defined by the boundary conditions at one endpoint, say, a, of the interval [a,b], comparing the value this solution takes at the other endpoint b with the other desired boundary condition, and finally increasing or decreasing λ as necessary to correct the original value. This strategy is not applicable for locating complex eigenvalues.

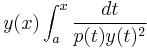

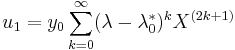

3. The Spectral Parameter Power Series (SPPS) method[3] makes use of a generalization of the following fact about second order ordinary differential equations: if y is a solution which does not vanish at any point of [a,b], then the function

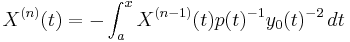

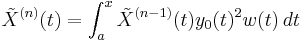

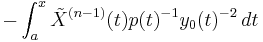

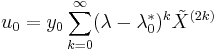

is a solution of the same equation and is linearly independent from y. Further, all solutions are linear combinations of these two solutions. In the SPPS algorithm, one must begin with an arbitrary value λ0* (often λ0*=0; it does not need to be an eigenvalue) and any solution y0 of (1) with λ=λ0* which does not vanish on [a,b]. (Discussion below of ways to find appropriate y0 and λ0*.) Two sequences of functions X(n)(t), X~(n)(t) on [a,b], referred to as iterated integrals, are defined recursively as follows. First when n=0, they are taken to be identically equal to 1 on [a,b]. To obtain the next functions they are multiplied alternately by 1/(py02) and wy02 and integrated, specifically

-

for n odd,

for n odd,  for n even,

for n even,(

-

for n odd,

for n odd,  for n even,

for n even,(

when n>0. The resulting iterated integrals are now applied as coefficients in the following two power series in λ:

and

and  .

.

Then for any λ (real or complex), u0 and u1 are linearly independent solutions of the corresponding equation (1). (The functions p(x) and q(x) take part in this construction through their influence on the choice of y0.)

Next one chooses coefficients c0, c1 so that the combination y=c0u0 + c1u1 satisfies the first boundary condition (2). This is simple to do since X(n)(a)=0 and X~(n)(a)=0, for n>0. The values of X(n)(b) and X~(n)(b) provide the values of u0(b) and u1(b) and the derivatives u0'(b) and u1'(b), so the second boundary condition (3) becomes an equation in a power series in λ. For numerical work one may truncate this series to a finite number of terms, producing a calculable polynomial in λ whose roots are approximations of the sought-after eigenvalues.

When λ= λ0, this reduces to the original construction described above for a solution linearly independent to a given one. The representations (5),(6) also have theoretical applications in Sturm–Liouville theory.[3]

Construction of a nonvanishing solution

The SPPS method can be itself used to find a starting solution y0. Consider the equation (p'y)'=μqy; i.e., q, w, and λ are replaced in (1) by 0, -q, and μ respectively. Then the constant function 1 is a nonvanishing solution corresponding to the eigenvalue μ0=0. While there is no guarantee that u0 or u1 will not vanish, the complex function y0=u0+iu1 will never vanish because two linearly independent solutions of a regular S-L equation cannot vanish simultaneously as a consequence of the Sturm separation theorem. This trick gives a solution y0 of (1) for the value λ0=0. In practice if (1) has real coefficients, the solutions based on y0 will have very small imaginary parts which must be discarded.

See also

- Normal mode

- Oscillation theory

- Self-adjoint

- Variation of Parameters

- Spectral theory of ordinary differential equations

References

- ^ J. D. Pryce, Numerical Solution of Sturm-Liouville Problems, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1993.

- ^ V. Ledoux, M. Van Daele, G. Vanden Berghe, "Efficient computation of high index Sturm-Liouville eigenvalues for problems in physics," Comput. Phys. Comm. 180, 2009, 532–554.

- ^ a b V. V. Kravchenko, R. M. Porter, "Spectral parameter power series for Sturm-Liouville problems," Mathematical Methods in the Applied Sciences (MMAS) 33, 2010, 459-468

Further reading

- P. Hartman, Ordinary Differential Equations, SIAM, Philadelphia, 2002 (2nd edition). ISBN 978-0-898715-10-1

- A. D. Polyanin and V. F. Zaitsev, Handbook of Exact Solutions for Ordinary Differential Equations, Chapman & Hall/CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2003 (2nd edition). ISBN 1-58488-297-2

- G. Teschl, Ordinary Differential Equations and Dynamical Systems, http://www.mat.univie.ac.at/~gerald/ftp/book-ode/ (Chapter 5)

- G. Teschl, Mathematical Methods in Quantum Mechanics and Applications to Schrödinger Operators, http://www.mat.univie.ac.at/~gerald/ftp/book-schroe/ (see Chapter 9 for singular S-L operators and connections with quantum mechanics)

- A. Zettl, Sturm–Liouville Theory, American Mathematical Society, 2005. ISBN 0-8218-3905-5.

![[(1-x^2)y']'%2B\nu(\nu%2B1)y=0\;\!](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/f60ced973c6cbb9b47259fe94dc1ef1f.png)

![L u = {1 \over w(x)} \left(-{d\over dx}\left[p(x){du\over dx}\right]%2Bq(x)u \right)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/95ed5e4bb6bac5f6accdb40ce1940c12.png)